Every movie awards season, the barrage of industry trade ads trying to solicit votes – sometimes for baffling causes – is coded by three simple, seemingly nonchalant words:

FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION

Generally your Consideration is pretty straightforward: a writer for a Screenplay nomination; a DoP for Cinematography and so on. But the awards bodies, particularly the Oscars, offer a major loophole, or rather black hole, to exploit in the Acting branches’ Lead and Supporting categories. This persistent gaming of the system has become known as –

Category Fraud: Misrepresenting a candidate’s work to increase their chance to win an award.

So let’s see how it works, with particular attention to two pretty shameless yet typical case studies from this year…

But first, a little Academy Awards background. When the Oscars were founded in 1928, there were no Supporting awards, just Best Actor and Actress. Supporting prizes, introduced in 1936, were seen as very much secondary – winners didn’t even get the statuette, they got… a plaque. I know. Control your excitement.

1944 revealed a systemic voting flaw, when actor Barry Fitzgerald was nominated in both Lead and Supporting categories for the same role in Going My Way. Fitzgerald went on to win Supporting (and co-star Bing Crosby won Lead), and soon after the rules changed to eliminate this problem. But if Fitzgerald’s doubling up was accidental, it showed how easy it could be to influence the nominations on purpose…

CATEGORY FRAUD NO. 1: FALSE MODESTY

In 1952, 20th Century Fox gambled on winning Richard Burton an Oscar for his Hollywood debut, My Cousin Rachel, pitching his romantic Lead as a Supporting. He got the nomination though not the win. But this dubious precedent is today practically the norm.

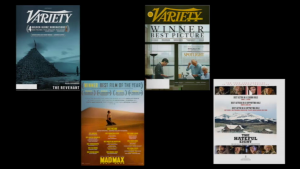

This year, it’s The Danish Girl’s female lead Alicia Vikander. Wary of 2015’s unusually strong Best Actress contenders, her campaign ads pushed her for Supporting. And since Academy rules only allow an actor to be nominated once per category, and for a specific role, Vikander’s excellent – and genuinely supporting – work in Ex Machina, a smaller independent film, missed the cut. Even if the media spin suggests that Vikander has merely replaced herself here, such category fraud usually results in denying other genuine candidates their shot.

Christoph Waltz, co-lead in Django Unchained, was initially touted as a Best Actor contender. When he switched to Supporting, he effectively knocked out the film’s real Supporting performers, Leonardo DiCaprio and Samuel L. Jackson. As did Tootsie’s female lead Jessica Lange, who beat her co-star and fellow Supporting nominee Teri Garr, much to Garr’s chagrin.

“I am thrilled about the nomination, but what really hurts is that I think Jessica Lange was the leading lady in Tootsie. I played the supporting role with the director telling me, ‘We can’t make you look too good in this movie’ and I was a real sport about it and then I have to share the nomination. Well, I am a little bugged by that.”

Teri Garr to Liz Smith, 1983.

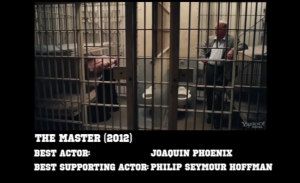

CATEGORY FRAUD NO.2: SPLIT PERSONALITY

Lange’s Tootsie roll to Supporting clearly had other motives, though, with that same year’s award potential playing the title character in Frances. Campaigners, then, might argue there was no choice but to push for one role per category (as braver, more honest campaigns for Vikander this year would have done). It’s rare that an actor has two good starring roles in one year, but when they do, and the campaigns manipulate so blatantly, as with Lange or Jamie Foxx in Ray (Lead) and Collateral (Supporting), it can look a little greedy.

CATEGORY FRAUD NO.3: DIVIDE AND CONQUER

Two co-stars, like Going My Way’s Crosby & Fitzgerald, competing against each other in the same Lead category used to be commonplace. The problem was, the pair regularly cancelled each other out, letting a rival beat them both to the prize. Since 1944, of the 15 occasions of dual Lead nominees, one of the pair went on to win the Oscar only 4 times.

Sadly, the odds of having your co-star by your side on stage – an acting tie has happened only twice in 85 years – was highly unlikely. So campaigners boxed clever. Since 1991, when both Geena Davis and Susan Sarandon’s Thelma and Louise lost Best Actress, no two co-stars have appeared in the same Lead category. Instead campaigners split candidates across Lead and Supporting, to avoid splitting the vote. Deliberately downgrading one party before even securing a nomination.

The excuses offered – “oh, well it’s X’s story as the film starts with him”, or “Y is the lead because her actions drive the narrative” – dupe only those needing to deceive themselves. What you often find is that the bigger star is campaigned as Lead, regardless of their size of role. So, Ethan Hawke’s hero and protagonist of Training Day, finds himself supporting Denzel Washington’s grandstanding villain Best Actor Oscar-winner.

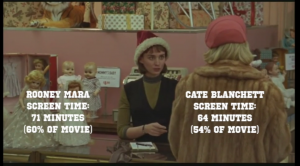

And that’s precisely the case with this year’s Carol. Patricia Highsmith’s novel ‘The Price of Salt’, on which the film is based, is told from Rooney Mara’s character Therese’s point of view. And though the film opens up this perspective, Mara still has screen time than co-star Cate Blanchett’s Carol. Mara even won the Best Actress award at Cannes, clearly seen there as supporting no one but herself.

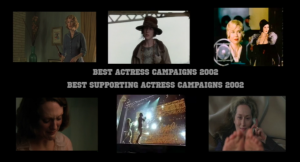

Campaigners The Weinstein Company’s logic is brutal but simple: avoid a head-to-head and potentially doubling the film’s chances. Cynical, sure, but proven to be effective. In 2002, the Weinsteins, then at Miramax, divvied up the three main actresses in The Hours, pushing Nicole Kidman and Meryl Streep as Leads and Julianne Moore as Supporting, despite the trio’s roughly equal screen time. This avoided clashing with Moore’s acclaimed rival starring turn in Far From Heaven, for which she did get a Lead Actress nomination, losing to Kidman. Streep, however, missed out on an Hours nomination, but ended up competing with Moore in the Supporting category for Adaptation. Yet they both lost to Catherine Zeta-Jones in Chicago – another Miramax release and “Supporting” performance that could easily have been considered Lead, but then would’ve competed against her co-star Renee Zellweger, who also lost to Kidman. Got all that?

The net result for Carol’s politicking is that Mara’s odds to win are now greatly increased. And placing her relative youth in Supporting, takes us neatly on to the third common category fraud:

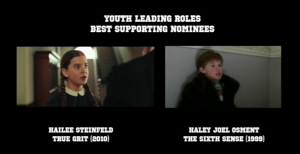

CATEGORY FRAUD NO.4: CHILD SUPPORT PAY-OFFS

A lesser issue, this, but a longstanding one. No matter how big a youngster’s role – and the likes of Tatum O’Neal in Paper Moon or Timothy Hutton in Ordinary People are clear leads – they would end up in the Supporting category. Both these actors actually won, and probably don’t feel so hard done by, but if a youth is thought good enough for awards, it seems patronizing at best to keep them in the lesser category. Recent examples of positive change do exist, but are still exceptions to the rule. Room’s amazing eight-year-old star Jacob Tremblay is at the centre of his film, and missed out on an Oscar nod. But it almost certainly would’ve come in the Supporting category (in which he received a Screen Actors Guild nomination), while his equally deserving co-star Brie Larson has long been the Best Actress frontrunner.

So how to crack down on such blatant scheming? A couple of obvious ideas spring to mind. Why restrict an actor to a single nomination per category? If they’ve given two great Lead or Supporting performances, allow voters the chance to put them forward twice. It can happen in any other category, where the likes of cinematographer Roger Deakins or director Steven Soderbergh have competed against themselves in the same year (Soderbergh, incidentally, won for Traffic, so the argument that you inherently split your own vote is immediately invalid).

Another idea is to judge category eligibility on the proportion of screen time. Current Academy rules flexibility practically encourages category fraud. Why not make it empirical? Anything over, say, 50% of screen time equals Lead; anything less, Supporting.

It’s tricky, though. One one hand, you avoid the farce of David Niven’s Best Actor Oscar for roughly fifteen minutes appearance in 1958’s Separate Tables. On the other, why not applaud Anthony Hopkins’s chutzpah pushing for inclusion as Best Actor for Silence of the Lambs when he’s onscreen for just over a quarter of the film’s running time. As the film’s biggest male character, his impact, onscreen and off, was pretty undeniable. And besides, do you want to keep time?

Also remember that voters aren’t forced to follow ad directives. In 2008, Kate Winslet was up for two films, Revolutionary Road and The Reader. Considered “overdue” for Oscar recognition, campaigns were run for Best Actress – Revolutionary Road – and Supporting for The Reader, a glaring case of category fraud. In the end, Oscar voters junked both the campaign recommendations and Revolutionary Road entirely, nominating Winslet as Best Actress for The Reader, which she duly won. But such bucking of the system is rare.

One should recognize too that this year’s Golden Globes voters placed both Alicia Vikander and Rooney Mara in their rightful Lead Actress category. Then again, the Globes can’t get too smug, as they also dutifully put sci-fi action adventure The Martian in their Best Picture Comedy or Musical. That The Martian then won, and that both Vikander and Mara lost, shows just why category fraud isn’t going away anytime soon. And, OK, “fraud” is pretty strong. This is the Oscars, not the sub-prime mortgage market. So feel free to soften the terminology. If the entire awards season is one big game anyway, these players surely feel they’re merely bending, rather than breaking the rules. Whether such ruthless calculations and machinations, more typical of today’s cynical and disrespectful political campaigns, is really worthy and worthwhile, well I guess that’s something best left…